Nearly 200,000 properties in England may have to be abandoned due to rising sea levels by 2050, a report says. It looks at where water will cause the most damage and whether defences are technically and financially feasible. There is consensus among scientists that decades of sea-level rise are inevitable and the government has said that not all properties can be saved. About a third of England’s coast will be put under pressure by sea-level rise, the report says. “It just won’t be possible to hold the line all around the coast,” says the report’s author Paul Sayers, an expert on flood and coastal risks, adding that tough decisions will have to be made about what it is realistic to protect “These are the places we are going to hold, and these are the places we’re not going to hold, so we need that honest debate around how we’re going to do that and support communities where they are affected.”

What to protect?

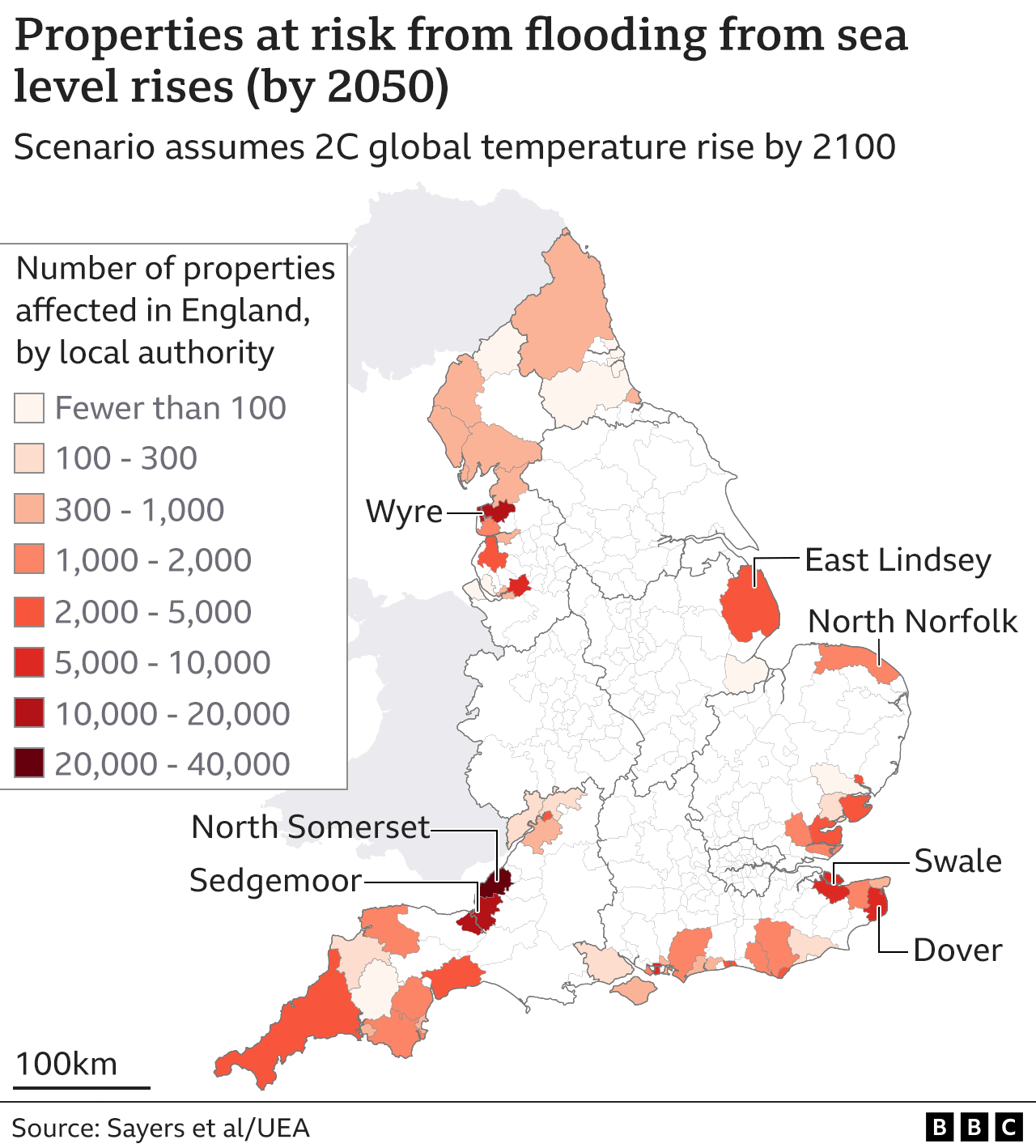

Sayers’ report lists the South West, the North West and East Anglia among parts of England with the highest number of properties at risk of flooding. Raised sea levels not only increase the risk of flooding on the coast and in estuaries but also accelerate coastal erosion through larger more powerful waves.

The study for the first time looks at places where the costs of improving defences may be too high or technically impossible. It found that by 2050 assuming a conservative sea-level rise caused by temperature increases of 2C by 2100, up to 160,000 properties are at risk of needing relocation. That’s in addition to between 30,000 and 35,000 properties that have already been identified as at risk.

“There’s no real engineering limit to how well we can protect ourselves, so for London for example, the Thames barrier and the all the walls and embankments, they continue to be raised in response to sea-level rise,” Sayers explained to BBC News on the beach at Happisburgh in North Norfolk. “There’s not going to be money, under current funding rules to protect everyone.”

Happisburgh’s dilemma

Happisburgh, a small picturesque old Anglo-Saxon village with a distinct red-and-white-striped lighthouse, is unlikely to receive any more money for sea defences. And its coast is already crumbling fast. The ground under Bryony Nierop-Reading’s bungalow fell into the sea in 2013 and there’s now a safety barrier across her street which ends abruptly at the top of the cliff. “Road Closed,” the red-and-white sign says. On it are handwritten dates and numbers where for the past six months the 77-year-old has been documenting the retreating tarmac. “Eight metres in December 2021, it’s 3.4 metres now,” she says with a sigh. Bryony has good reason to monitor the erosion. When her bungalow was demolished, she chose to move just 50m up the road to a house that is also destined to crumble into the sea. “It’ll probably last until 2030,” she says. Bryony does not accept the decision from the district council that Happisburgh should not be protected by new sea defences. She points out where large amounts of sand have been dumped on the shore to protect a gas terminal.

“It’s just such a feeble and unpatriotic attitude,” she says. “I think that we should be saying that our country, our land, our agricultural land, is sufficiently important that we need to divert funding to it.” Bryony has launched an organisation to try and attract renewed interest in some new sea defences. “It’s the Save Happisburgh Action Group,” she tells me. “The name Shag makes people snigger but a shag is a seabird who has to fight for survival against impossible odds. That’s very appropriate for Happisburgh.”

“Roll-back”

Bryony’s view is not universally held in Happisburgh. And hers is not the only campaign group. “The sea is very powerful. Even more powerful than Boris Johnson,” says the booming voice of Malcolm Kirby, one of the founders of Happisburgh’s Coastal Action Group. Malcolm is 81 and has been involved in finding a solution for Happisburgh’s erosion problem for more than 20 years. Back in 2009, he helped devise a government-backed “Pathfinder” project whereby the owners of homes that were about to fall into the sea were offered market price by the government and helped to resettle further inland. He calls it “roll-back”. “You either commit to spending billions over an extended period,” he says. “Or you say OK in the light of what’s coming with climate change and sea-level rise we will do a properly managed withdrawal and look after the people as we go.”

Pilot project

Happisburgh’s Pathfinder project is now being looked at as an example of how the rest of the UK might adapt. Along with East Yorkshire, north Norfolk has been chosen to be part of a £36m Coastal Transition Accelerator Programme which will look at ideas such as establishing “green buffer zones” between communities and facilitating the “managed transition of communities from high-risk land”.

At Happisburgh’s pub, landlord Clive Stockton says the realisation that the village will slowly fall into the sea casts a long shadow. “As soon as the decision is made that there is no defence, then all normal commercial transactions, whether it be commercial loans for businesses or insurance stop existing,” he says. “The problem doesn’t just start when the properties start to go over the cliff.” Clive believes there’s a middle ground and would like to see a mix of relocation and defence to slow the sea’s advance. “Inevitable is a long way away,” he says. “Climate change was created by the whole human race over the last 40 or 50 years.

![]()