University staff is walking out on Thursday on the first of three days of strikes over pay, working conditions, and pensions. Lectures could be called off at 150 affected universities. The National Union of Students is supporting the strikes, but some students are concerned about missing classes.

Universities say they will put measures in place to mitigate the impact on students’ learning. The University and College Union (UCU) says more than 70,000 staff will be taking part in the strikes, which also take place on Friday and next Wednesday. It is unclear how much teaching will be called off, as union members do not have to say whether they will be striking.

‘Exhausted’

Student Katherine Greenstein, 19, feels lecturers are “exhausted” so will be joining the picket lines at Queen’s University Belfast. “I have never seen a lecturer not have a cup of coffee or a cup of tea with them,” Katherine told the BBC. “These people give their all to support you every single day of the academic year, and you get you’re being asked to get a day off from class and to turn around and support them for three days. Why wouldn’t you jump at that opportunity?”

Katherine, who uses the pronouns they/them, is a student from the US, and is paying more than $20,000 (£16,600) per term to study in the UK on a year abroad. It means that the missed class is worth even more, in monetary terms, than it is for British students. “I believe that the value of the human being teaching that class is infinitely more than whatever the material is that they were going to teach me,” they said.

‘We are customers’

But Billie Early, a 23-year-old Masters student at the University of Sussex, feels that students are not getting a good “deal” because of the disruption. Her undergraduate degree was disrupted by strikes and Covid, and now she is missing a seminar on Friday because of this walkout, she said. “We are paying customers. We’re not getting what we paid for,” she said. “For a part-time Masters in a humanity subject, you don’t have many contact hours… and then they take that away from you.” Ms Early said the strikes bring back a feeling of being “on your own”, which she experienced when in-person teaching stopped during Covid. “I understand why they are striking,” she said. “But I just feel that maybe lecturers should reach out to students, and emphasise and reassure us that they do want to be there for us. Because I’m just not get getting that from them.”

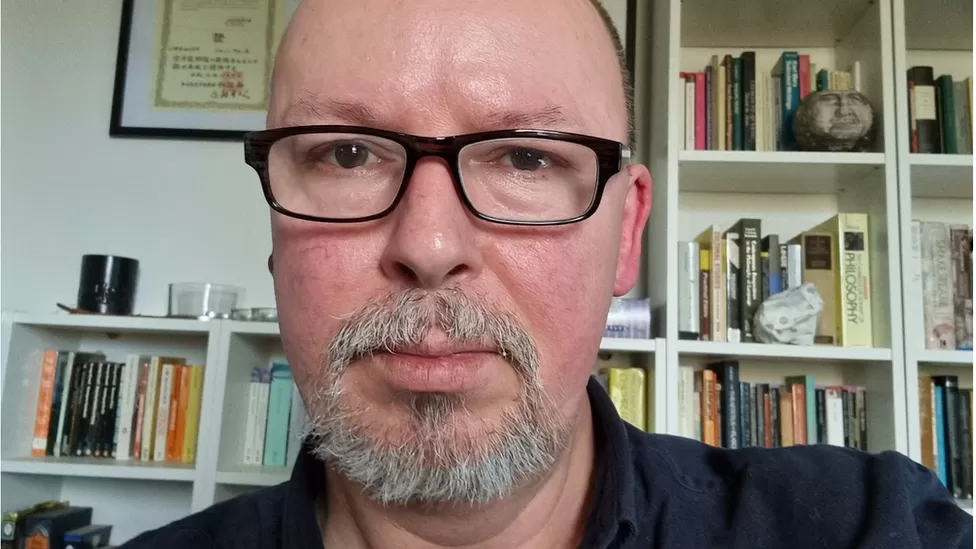

The University of Sussex said it was “very concerned” about its students, and that measures to “minimise the impact of the strike” included rescheduled teaching and extra materials. Sean Broome, who lectures in education at the University of Derby and is the chair of the UCU branch there, says it is unfair that staff pay has fallen in real terms while universities spend money elsewhere. Colleagues of his are being asked to take on more work, he said, such as admin tasks and teaching extra modules. “We earn less than we have done, even though the figure hasn’t gone down,” he said, adding that his own pay has remained roughly the same for about 10 years.

“The greatest asset of a university isn’t buildings and infrastructure, it’s their staff, really. And who wants a staff that is overworked, under-motivated and underpaid?” Working conditions have led to a “lack of motivation” among staff, he said – and uncertainty for some of his colleagues who have been on zero-hour contracts for as long as five years. He sympathises with students whose learning would be disrupted, but added: “Our message, of course, is that they should contact the university and and ask why we’re needing to strike.”

‘Even Bigger Action’

UCU general secretary Jo Grady called it “the biggest strike action in the history of higher education”, with the union estimating that 2.5 million students could be affected. “University staff… have had enough of falling pay, pension cuts and gig-economy working conditions – all whilst vice-chancellors enjoy lottery win salaries,” she said. She said further disruption could be avoided if concerns were “addressed with urgency”, and added that, if not, “even bigger action” would follow next year.

The UCU is demanding a pay rise of inflation (RPI) +2%, or 12%, whichever is higher, as well as an end to zero and temporary contracts and action to tackle “excessive workloads”. The dispute over pensions has been rumbling on for more than a decade, and was reignited by what the UCU said was a “flawed” valuation of a pension scheme used by academic staff. It said the average member “will lose 35% from their guaranteed future retirement income”.

Prof Steve West, president of Universities UK and vice-chancellor of UWE Bristol, said the scheme “remains one of the most attractive private pension schemes in the country”. He said students may be worried by further disruption, adding: “Universities are well prepared to mitigate the impact of any industrial action on students’ learning, and we are all working hard to put in place a series of measures to ensure this.” Many universities were unable to say what their mitigations would involve when contacted by the BBC, but some stressed that student services and libraries would remain open, and classes would be rescheduled where appropriate.

Raj Jethwa, chief executive of the Universities and Colleges Employers Association, said the UCU’s pay demand was “unrealistic”. “Strike action does not create new money for the sector,” he said. Chloe Field, vice-president for higher education at the National Union of Students, said it was supporting the strikes because “staff working conditions are students’ learning conditions”. Higher education minister Robert Halfon said it was “hugely disappointing” that students would face further disruption, and urged “all sides to work together”.

![]()