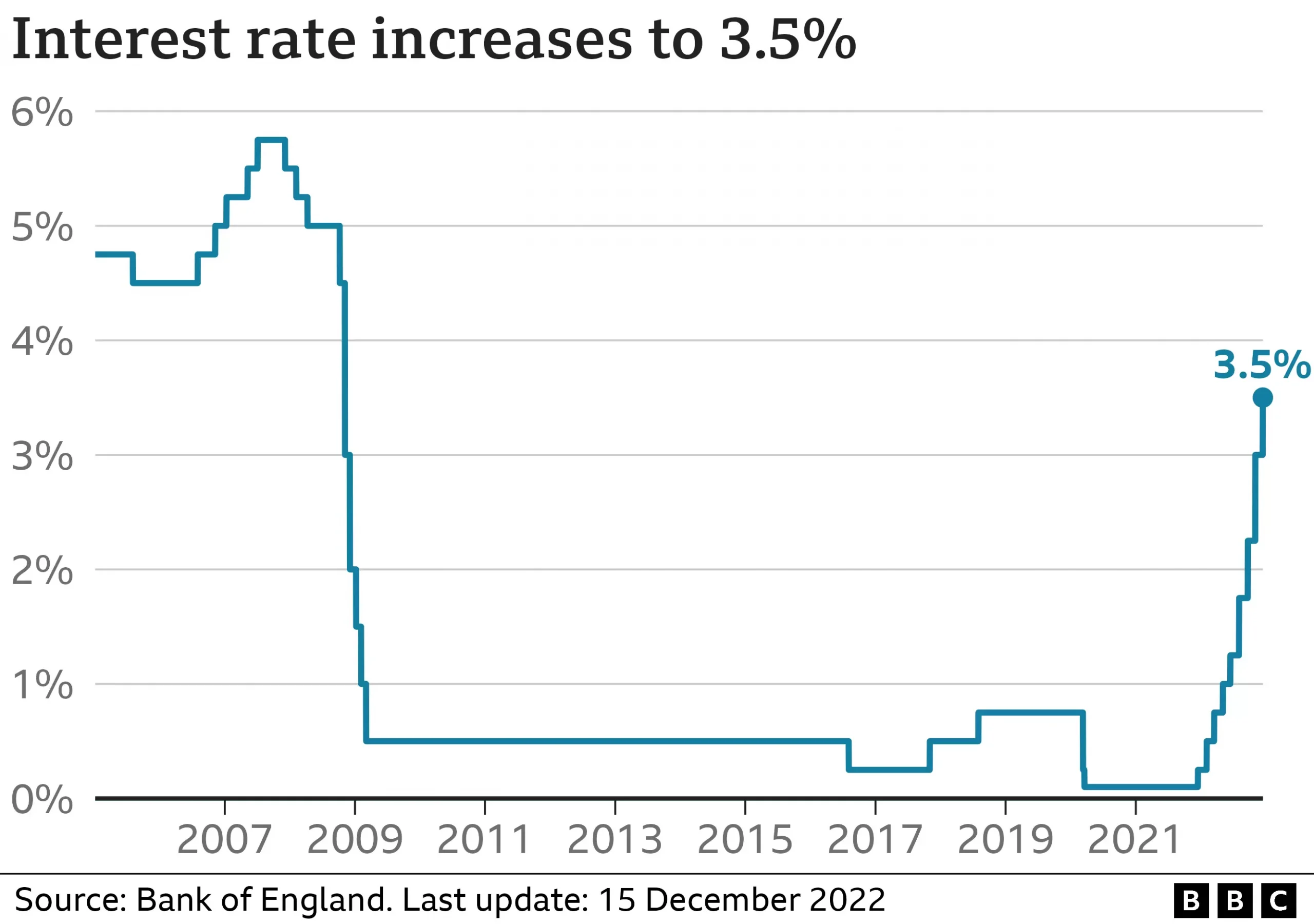

The Bank of England has raised UK interest rates to their highest level for 14 years as it battles to stem soaring prices. It increased them to 3.5% from 3%, marking the ninth time in a row it has hiked interest rates. The rise will mean higher mortgage payments for some homeowners and those with loans at a time when many people are struggling with the cost of living. It should also benefit savers if banks pass on the higher rate to customers.

Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey said it was the “first glimmer” that soaring price rises were starting to come down but there was still “a long way to go”. Announcing its latest rise, the Bank indicated it was likely to continue to increase interest rates next year. It means that homeowners with variable rate mortgages or first-time buyers looking to get on the property ladder could face higher costs. Following the most recent rate rise, people on a typical tracker mortgage will pay about £49 more a month while homeowners with a standard variable rate mortgage face a £31 jump.

‘My mortgage has gone up by £120’

Clive Turner, who works in customer services, is one of many borrowers hit by rising rates as their fixed rate mortgage deal comes to an end. He and his partner were paying a rate of 3.48% before their five-year deal expired, amounting to payments of around £628 a month. But the 48-year-old is now paying 5.76% on a new fixed-rate deal with payments of £750 a month – a £120 increase. His gas and electricity bills have also gone up, he said. “I just wanted to fix it, take the hit, and hopefully at the end of the five years we will get something better,” he said. Mr Bailey said: “I know that high interest rates have a real impact on people’s lives but by raising interest rates we can bring inflation down sooner.”

The Bank’s rate-setting committee expects inflation to fall “quite sharply” by the middle of next year. “Raising rates is the best way we have of making sure that happens,” he said. The Bank of England has to balance increasing borrowing costs without causing the economy to slow too much.

The UK is already believed to be in recession due to the impact of soaring prices on businesses and consumers. A recession is defined as when a country’s economy shrinks for two three-month periods – or quarters – in a row. Typically, companies make less money, pay falls and unemployment rises. This means the government receives less money in tax to use on public services such as health and education. However, the Bank said it believed the economy would perform better than expected between October and December – shrinking by 0.1% in the final three months of the year rather than 0.3% as previously thought. It comes as millions of people are under pressure as the cost of living rises and wages fail to keep up. Regular pay grew by 6.1% in the three months to October, according to the latest official figures. But taking inflation into account, wages actually fell by 2.7%.

‘Tough times’

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt said high inflation was a global problem and indicated raising public sector pay could make the situation worse. Anger over how it has lagged behind soaring prices has led to widespread strikes. “I know this is tough for people right now, but it is vital that we stick to our plan, working in lockstep with the Bank of England as they take action to return inflation to target,” he said. “The sooner we grip inflation the better. Any action which risks permanently embedding high prices into our economy will only prolong the pain for everyone, stunting any prospect of economic recovery.” But Labour’s shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves said today’s rate hike was further evidence the government had lost control of the economy. She accused the Conservatives of “harming growth, and leaving millions of working people paying a Tory mortgage penalty for years to come”. Defending its latest rate hike, the Bank said it had seen evidence of firms raising wages to recruit workers and warned if this continued it would require it to raise interest rates faster and further.

In total six of the nine Monetary Policy Committee members who decide on interest rates voted in favour of the rise to 3.5%. However, two others said it was now time to halt rate rises entirely, while one argued for an even sharper increase. Other countries have also been putting up interest rates to tackle soaring inflation. On Wednesday, the US central bank increased the target range for its benchmark rate by 0.75 percentage points to 4.25%-4.5% – the highest it has been in 15 years. And on Thursday, the European Central Bank put up rates for countries that use the euro by half a percentage point to 2.5%. While rates are set to go higher, there is a sense from the Bank of England’s deliberations that the medicine is starting to work, so they have lowered the dosage.

The Bank has followed its US counterpart in raising rates by half a percentage point, but did not choose its path of four consecutive 0.75% rises before that. Britain had a brief one-off experience of such jumbo rate hikes last month. What does that tell us? That the final resting level of interest rates in the UK will be closer to 4%. It will likely be reached in the middle of next year, and stay there for some time. However, the stark impact of higher rates is already being felt. The Bank noted some sharp monthly falls in house prices, and that fixed mortgage rates – while down from their mini-budget crisis highs – remained elevated.

![]()