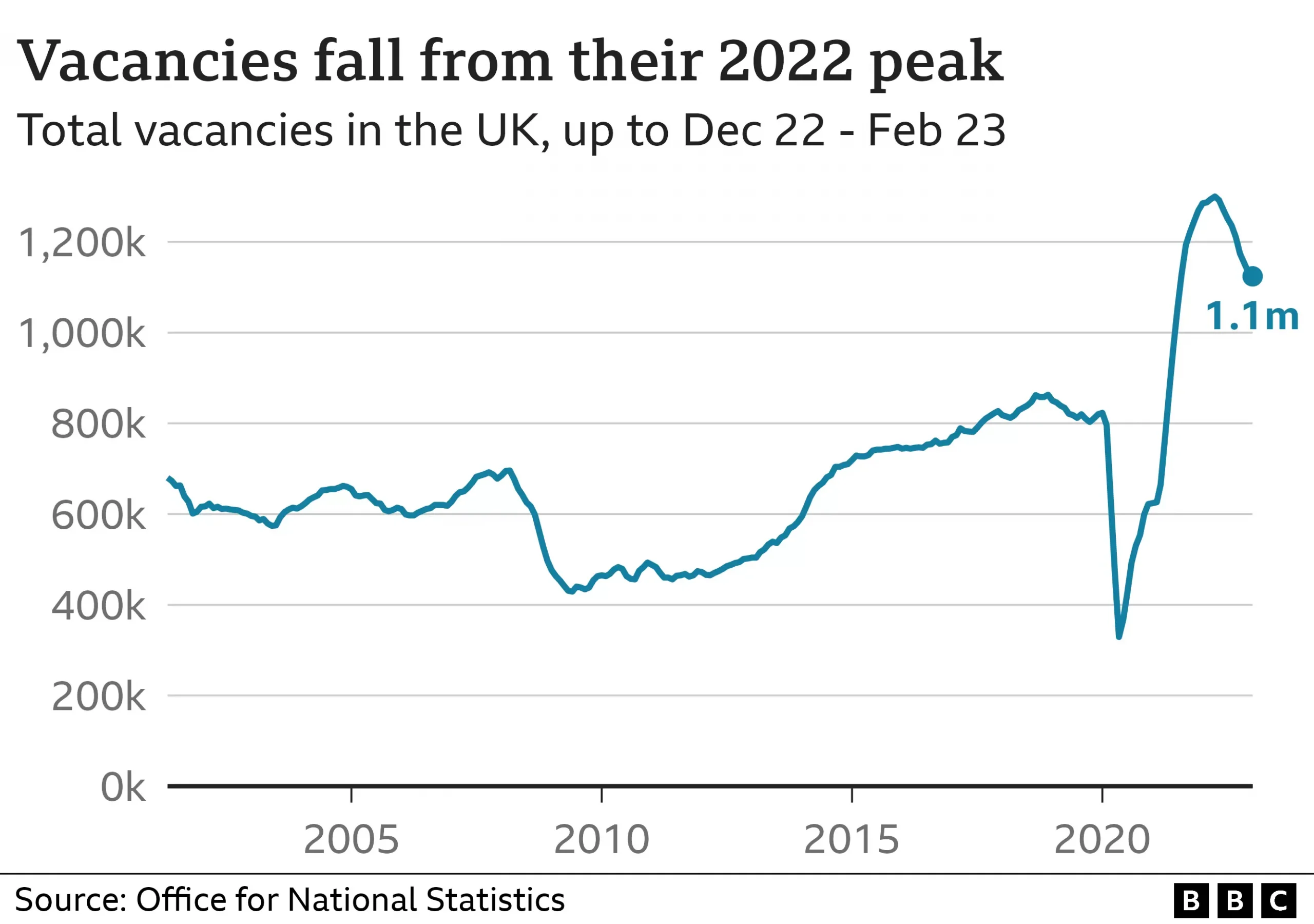

Job vacancies in the UK have fallen for the eighth time in a row as companies blamed economic pressures for holding back on hiring new staff. The official figures come a day ahead of Wednesday’s Budget when the chancellor is expected to set out plans to encourage people back into work. The number of jobs on offer between December and February fell by 51,000 compared with the three months before. Despite the drop, the number of job vacancies remains high at 1.1 million. There are also 328,000 more vacancies compared to the pre-pandemic period of between January and March 2020.

The rate of economic inactivity – people aged between 16 to 64 who are not in work and not seeking a job – dipped to 21.3% between November and January. This was driven by younger people aged between 16 to 24 either getting jobs or looking for work. However, there are still nine million economically inactive Britons who are not part of the workforce either because they are students, have retired or are suffering from long-term illness. On Wednesday, it is anticipated that Chancellor Jeremy Hunt will detail how the government intends to entice people back into work. One measure expected to be announced is a boost to the amount that people can save for their pensions before it is taxed.

Danni Hewson, head of financial analysis at AJ Bell said this move was “an incredibly welcome start”, but added: “It does little to address labour issues at the lower end of end of the scale.” James Reed, chairman of recruitment firm Reed, said that while there was a fall in new jobs “it’s not cause to panic”. He told the BBC’s Today programme: “Actually there are over 300,000 more vacancies than there were this time pre-pandemic, three years ago, so the labour market is pretty buoyant still which is surprising many people.” Robin Clevett, a self-employed carpenter and joiner who manages up to 10 subcontractors on construction projects, said that he was having to turn down work because there are not enough skilled workers available.

“Business is really buoyant at the moment,” he told the BBC. “Everyone needs trades – they need people to do insulation work, they need people to do new builds, refurbish old builds, replace cladding. There’s so much work but there’s not enough labour to go around so that’s what has driven this massive demand and adverts everywhere for all kinds of trades.” He added: “I personally won’t take on work now knowing I’m not going to find the staff. So I’m turning down opportunities.”

On the eve of the chancellor’s so-called “back to work” Budget, the official numbers show that is already beginning to happen. Employment has risen again, but this time driven by part-time and the self-employed. While vacancies have fallen they still remain very high. Wages are growing in cash terms versus last year but by still well below the inflation rate. On a month-to-month basis though, there is some evidence that pay growth is starting to stall. With unemployment still very low by international standards, and employment high, the jobs market remains a bright spot in the figures. This has underpinned a consumer more resilient than might be expected to the massive energy price shock.

With the global financial system exhibiting some fragility after bank collapses in the US, the Bank of England could decide to hold off on further rate rises next week. Meanwhile, pay growth appeared to be stalling, according to the data from Office for National Statistics.

The average weekly salary in the UK, excluding bonuses, in January stood at £589, up by £1 on a month before. Throughout 2022, the average salary rose by nearly £3 a month. That was not enough to keep up with the cost of living. The average salary fell by 2.4% in the three months to January compared to the same period last year after taking account rising prices, or inflation. While the rate of inflation is falling, it remains high at 10.1%.

Darren Morgan, director of economic statistics at the ONS, said: “Although the inflation rate has come down a little, it’s still outstripping earnings growth, meaning real pay continues to fall.” The ONS also detailed that there were 220,000 working days lost to strike action in January. However, this was far lower than 822,000 recorded in December when widespread industrial action hit areas such as postal deliveries and train services.

![]()