Rishi Sunak has said he is “up for the fight” to bring in new legislation to prevent migrants from crossing the Channel on small boats to reach the UK. The prime minister said he was confident the government would win any legal battles over the “tough, but necessary and fair” measures. Earlier his home secretary, Suella Braverman, announced the bill during a divisive debate in Parliament. Labour said the Tories’ latest plans were like “groundhog day” and a “con”. It is not just opposition MPs who have cricriticizede plans. The UN’s refugee agency, the UNHCR, said the proposed legislation amounted to an “asylum ban”.

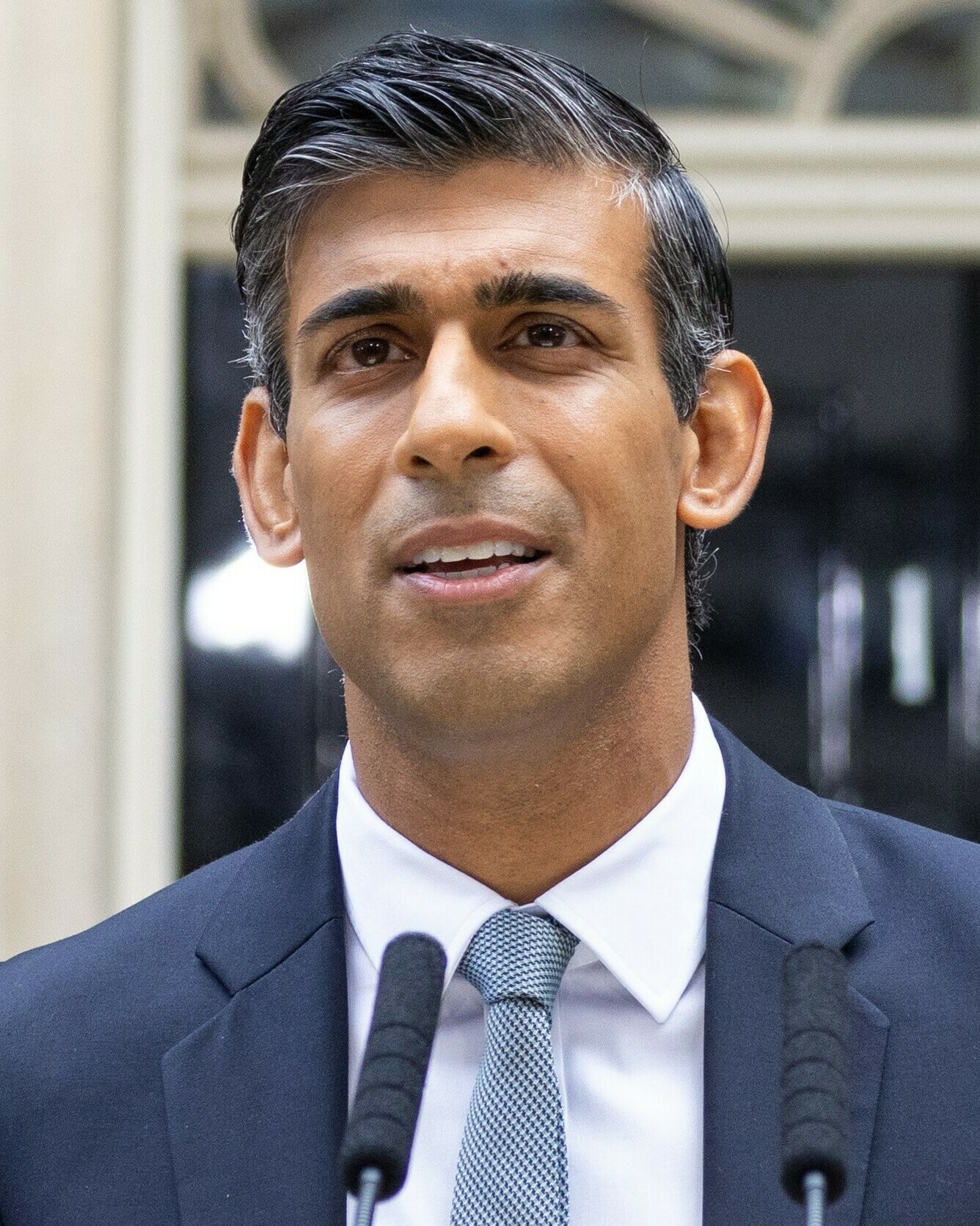

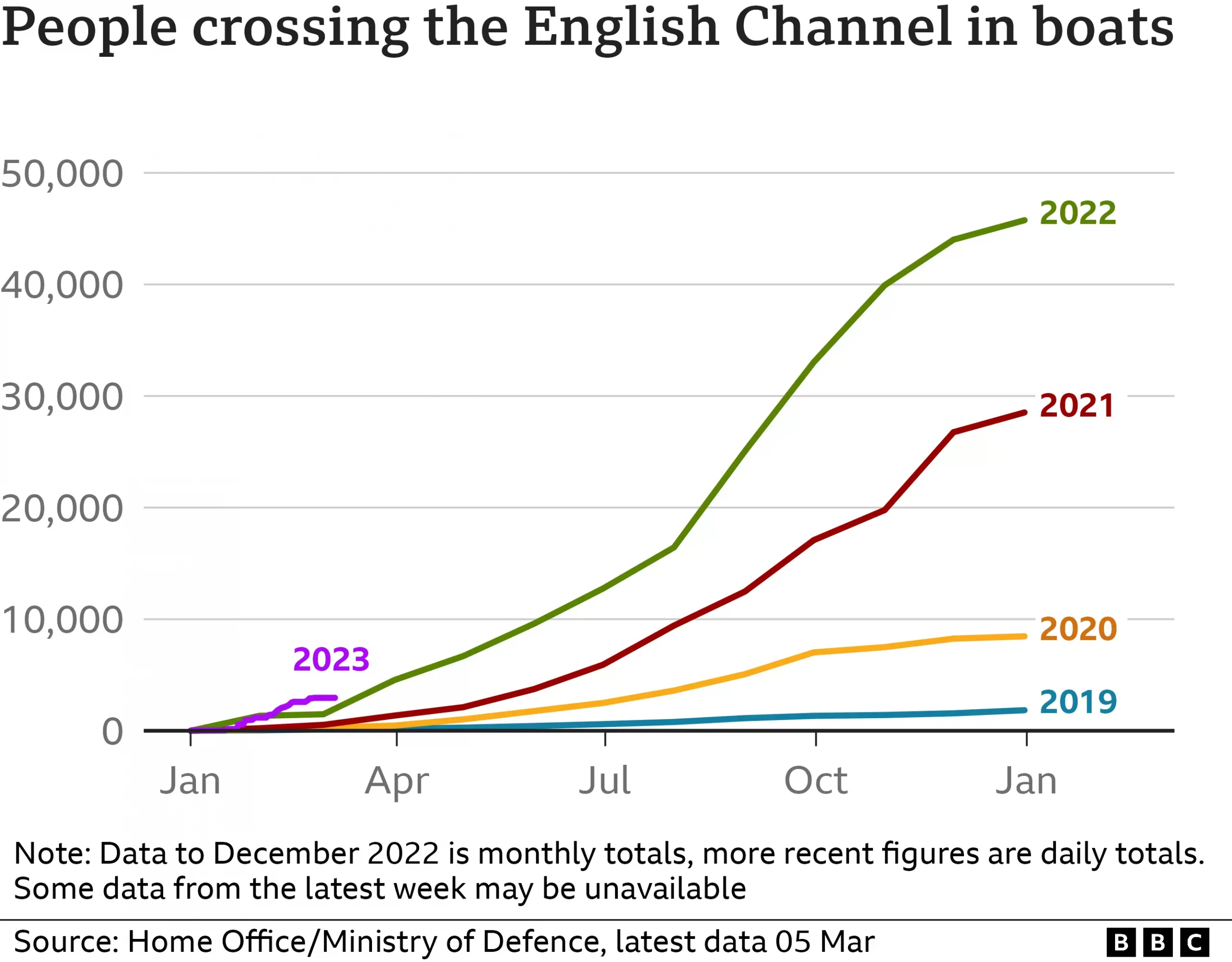

Standing behind a lectern emblazoned with the slogan “stop the boats”, Mr. Sunak confirmed the planned new law, which will see illegal migrants deported “within weeks”, would apply retrospectively to everyone arriving in the UK illegally from Tuesday. He said he knew there would be a debate about the toughness of the Illegal Migration Bill but the government had tried “every other way” of preventing the crossings and they had not worked. While he admitted it was a “complicated problem” with no single “silver bullet” to fix it, he said he would not be standing there if he did not think he could deliver. More than 45,000 people entered the UK via Channel crossings last year, up from about 300 in 2018.

The government believes stopping small boats is a key issue for voters and Mr Sunak has made it one of his top five priorities. This is politically risky – as the outcome may not be entirely in his hands. Speaking in the Commons, shadow home secretary Yvette Cooper said serious action was needed to stop small boat crossings, but said the government’s plans risked “making the chaos worse”. Opposition MPs attacked the legislation one after another, with some saying it was unlawful, while others suggested it would not work in practice. But Tory MPs backed their home secretary as they took turns to welcome the move, and Ms Braverman retorted that Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer “doesn’t want to stop the boats”.

Trying to set out the scale of the problem the home secretary said 100 million people around the world could qualify for protection under current UK laws – and “they are coming here”. This refers to a UNHCR figure that there are more than 100 million people forcibly displaced around the world, although there is nothing to suggest they would all want to come to the UK. Acknowledging the likelihood of a legal battle, Ms Braverman wrote to Conservative MPs saying there was “more than a 50% chance” the legislation was incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

This potentially makes legal challenges – and a rough ride for the bill in the Lords – more likely. But the political calculation could well be that the new legislation puts clear blue water between government and opposition. And if the bill is stymied, the prime minister may be hoping he gets some political credit from voters for trying to find a solution. Mr Sunak told a Downing Street conference he believed it would not be necessary for the UK to leave the ECHR and said the government believed it was acting in compliance with it and “meeting our international obligations”. He said part of the problem was people making one claim “then down the line they can make another claim, and then another claim” and said the UK cannot have a system which could be taken advantage of.

The deterrent effect of the new legislation could be “quite powerful quite quickly”, he added.

Under the new bill:

- People removed from the UK will be blocked from returning or seeking British citizenship in future

- Migrants will not get bail or be able to seek judicial review for the first 28 days of detention

- There will be a cap on the number of refugees the UK will settle through “safe and legal routes” – set annually by Parliament

- A duty on the home secretary to detain and remove those arriving in the UK illegally, to Rwanda or a “safe” third country – this will take legal precedence over someone’s right to claim asylum

- Under-18s, those medically unfit to fly, or those at risk of serious harm in the country they are being removed to will be able to delay removal

- Any other asylum claims will be heard remotely after removal

The UN’s refugee agency, the UNHCR, said it was “profoundly concerned” by the bill, calling it a “clear breach” of the refugee convention. “Most people fleeing war and persecution are simply unable to access the required passports and visas,” it said. “There are no safe and ‘legal’ routes available to them. Denying them access to asylum on this basis undermines the very purpose for which the Refugee Convention was established.” The Refugee Council said it was “not the British way of doing things”, with its chief executive Enver Solomon saying the plans were “more akin to authoritarian nations”, while Amnesty International called it a “cynical attempt to dodge basic moral and legal responsibilities”.

![]()