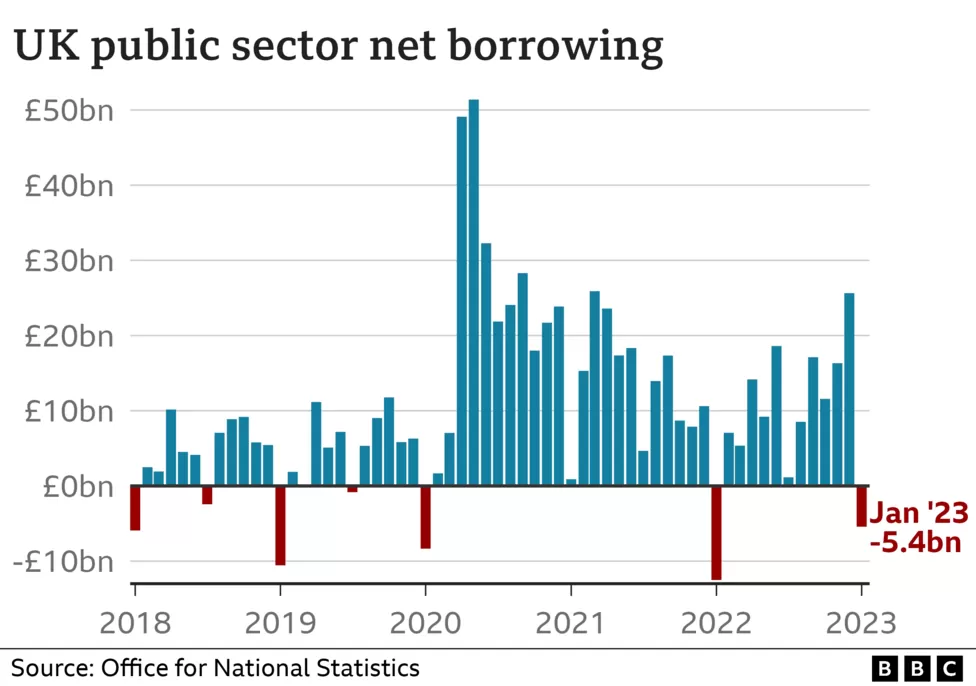

The UK government saw a surprise surplus in its finances in January despite “substantial spending” to help with energy bills and EU payments. The highest self-assessed income tax receipts since records began in 1999 boosted the UK’s coffers. It meant it spent less than it received in tax, leaving a £5.4bn surplus. Economists said the figures showed a “mixed picture” with public finances still weaker than this time last year ahead of next month’s Budget.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt will set out his plans for tax and spending on 15 March. Martin Beck, the chief economic advisor to the EY ITEM Club which is a UK economic forecasting group, said the figures gave Mr. Hunt “some positives to work on” in his Budget. Mr. Beck said the fall in the cost of wholesale energy meant the government’s spending on support for bills “will be a fraction” of what was officially forecast last year. However, because the government’s self-imposed fiscal rules around debt relate to five years in the future, he said short-term movements in UK’s finances “don’t have much bearing” on policies.

Public borrowing in the financial year to date is £30.6bn less than predicted by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the government’s official forecaster. Michal Stelmach, senior economist at KPMG UK, said this could “tempt the chancellor to offer a pay increase to public sector workers as part of his Budget next month” in a bid to prevent further strikes. But Mr Hunt said debt was still at the highest level since the 1960s. “It is vital we stick to our plan to reduce debt over the medium term,” he added. “Getting debt down will require some tough choices, but it is crucial to reduce the amount spent on debt interest so we can protect our public services.”

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s spokesman later indicated the surplus did not mean it would announce tax cuts at the Budget. “We shouldn’t place too much emphasis on a single month’s data. Borrowing remains at record highs and there is significant uncertainty and volatility, both clear risks to the fiscal position,” the spokesman said. Every January, the government tends to take more in tax than it spends in other months due to the amount it receives in self-assessed taxes, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS). But most economists had expected borrowing to rise this time, in part due to the large amount the government is spending on supporting households with their energy bills. It is limiting the average household energy bill to £2,500 – although it says this will increase to £3,000 from April due to the high cost of the support.

In addition, the ONS said the government had faced “large one-off payments” in January relating to historic customs duties owed to the EU. In the end, though, these costs were largely offset by record self-assessed income tax payments of £21.9bn in January, which left the government with a surplus. It’s not just an unexpected surge in tax receipts from the self-employed that caught most economists on the hop this morning, resulting in a surplus instead of the anticipated deficit. Separate figures published this morning by HMRC show the amount received in tax and national insurance in the financial year to date was £368.5bn – a huge increase of £44.9bn compared to the same period a year earlier.

The government points out that debt (ie all the accumulated borrowing over the years) is at its highest since the 1960s and says it will require “tough choices”. But there’s no doubt that the public finances are under much less pressure – £31bn less – than the OBR anticipated in November. Amid calls, for example, to spend £2.6bn preventing a further rise in energy bills, or more money to alleviate the recruitment crisis in the NHS, an argument that any of those measures is “unaffordable” in any objective economic sense isn’t given any obvious support in the data. But despite the surprise figures, January’s overall surplus was still £7.1bn smaller compared to the same month in 2022. Interest repayments on government debt also hit their highest level for January since records on that data began in 1997.

The ONS said the rise in debt repayments, which totalled £6.7bn in January, was “largely” because of inflation. This is because many UK government bonds, or “gilts”, which the government sells to international investors to raise the money it needs, are “index linked”, meaning the government’s repayments rise in line with the Retail Prices Index (RPI) measure of inflation, which is currently at double-digit levels. Of the interest payable in January 2023, some £3.3bn reflected the impact of inflation, the ONS said.

![]()